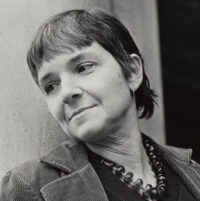

1978 Dichter Adrienne Rich

Adrienne Rich (1929-2012) is een van de meest invloedrijke en gelezen dichters van de afgelopen 50 jaar. Dat geldt voor Amerika, maar zeker ook in Nederland. Zowel uit haar gedichten als haar essays spreekt een diepe bewondering voor de geschriften van Emily Dickinson. Niet alleen voor haar eigenzinnige stijl van schrijven maar ook voor haar sterke persoonlijkheid als vrouw binnen een patriarchale cultuur.

Adrienne Rich (1929-2012) is een van de meest invloedrijke en gelezen dichters van de afgelopen 50 jaar. Dat geldt voor Amerika, maar zeker ook in Nederland. Zowel uit haar gedichten als haar essays spreekt een diepe bewondering voor de geschriften van Emily Dickinson. Niet alleen voor haar eigenzinnige stijl van schrijven maar ook voor haar sterke persoonlijkheid als vrouw binnen een patriarchale cultuur.

Adrienne Rich voelt zich sterk met haar verbonden en zo geraakt door haar kracht dat ze gedichten voor haar is gaan schrijven.

In 1862 stuurt Emily Dickinson enkele gedichten naar Thomas Higginson, een bekend schrijver. Ze heeft in een tijdschrift een stuk van hem gelezen over jonge schrijvers. Ze wil weten wat hij van haar gedichten vond. Wat hij precies geantwoord heeft weten we niet, wel dat hij de nodige kritiek op haar werk geeft. Emily Dickinson vindt dat hij als een chirurg haar werk ontleedt. Maar juist zijn kritiek stimuleert haar door te gaan met haar eigen stijl van schrijven. Opvallend dat na haar dood Thomas Higginson samen met Mabel Todd en haar zus Lavinia meewerkt aan de publicatie van haar gedichten. In die publicatie zijn diverse gedichten door hen bewerkt en aangepast.

Honderd jaar later, in 1964, schrijft Adrienne Rich een gedicht aan Emily Dickinson, waarin zij verwijst naar de betrokkendheid van Thomas Higginson bij de postume publicatie van haar gedichten. Zij vindt het een “verminking” van de Dickinson-poëzie. Als titel voor haar gedicht gebruikt Adrienne Rich een zin die rechtstreeks overgenomen is uit de brief van Dickinson aan Higginson (Brief 265):

“I am in Danger – Sir”

“Half-cracked” to Higginson, living,

afterward famous in garbled versions,

your hoard of dazzling scraps a battlefield,

now your old snood

mothballed at Harvard

and you in your variorum monument

equivocal to the end

who are you?

you, woman, masculine

in single-mindedness,

for whom the word was more

than a symptom

a condition of being.

Till the air buzzing with spoiled language

sang in your ears

of Perjury

and in your half-cracked way you chose

silence for entertainment,

chose to have it out at last

on your own premises.

(Uit: From Necessities of Life, Norton Books, 1966)

Het belangrijkste essay van Adrienne Rich over Emily Dickinson heet Vesuvius at Home:The Power of Emily Dckinson (1975). Ze beschrijft daarin hoe Emily Dickinson haar geholpen heeft in haar eigen zoektocht als vrouw en lesbiënne in een door mannen beheerste maatschappij. Ze wil begrijpen hoe zij als vrouwelijke dichter in een patriarchale samenleving kon leven. De oplossing van Emily Dickinson, zo concludeert ze, ligt in het bewust inrichten van haar leven om haar gaven als dichteres zo goed mogelijk tot uitdrukking te laten komen. Zij heeft zelfbewust gekozen voor een leven dat op haar voorwaarden was ingericht. Ze blijft ongehuwd, kiest zelf haar relaties, woont op zichzelf, schrijft gedichten in een eigen stijl, werkt in haar tuin, vormt haar eigen mening, en ontwikkelt een eigen spiritualiteit.

Zo bezien is Emily Dickinson niet langer het excentrieke, passieve wezen dat men ooit van haar dacht, maar staat ze als een sterke vrouw die haar gave ontwikkelt zoals zij het wilt. Voor Adrienne Rich is zij een pionier die het domein van het geschreven leven voor vrouwen ontdekt – het essay is te vinden in Adrienne Rich’s Poetry And Prose, Norton Books, 1993, p. 175-195).

Vol bewondering is zij over hoe Emily Dickinson, levend in een sterk partriarchale cultuur, er toch in slaagt als vrouw haar eigen weg te gaan: “her choice to be, not only a poet but a woman who explored her own mind, without any of the guidelines of orthodoxy. To say “yes” to her powers was not simply a major act of nonconformity in the nineteenth century; even in our own time it has been assumed that Emily Dickinson, not patriarchal society, was “the problem.” The ore we come to recognise the unwritten and written laws and taboos underpining patriarchy, the less problematical, surely, will seem the methods she chose.” (Uit Adrienne Rich, On Lies, Secrets, and Silence. Selected Prose 1966-1978, Norton Books, 1995).

In de zestiger jaren gaat Adrienne Rich samen met haar vriendin Michelle Cliff in de buurt van Amherst wonen, de streek van Emily Dickinson. Daar schrijft ze haar laatste gedicht voor Emily Dickinson: The Spirit of Place. Het is bijzonder ontroerend. Delen van het gedicht zijn gericht aan haar geliefde en delen van het gedicht zijn gericht aan Emily Dickinson. Er is een opname dat ze het gedicht zelf voordraagt.

The Spirit of Place

Voor Michelle Cliff

I.

Over the hills in Shutesbury, Leverett

driving with you in spring road

like a streambed unwinding downhill

fiddlehead ferns uncurling

spring peepers ringing sweet and cold

while we talk yet again

of dark and light, of blackness, whiteness, numbness

rammed through the heart like a stake

trying to pull apart the threads

from the dried blood of the old murderous uncaring

halting on bridges in bloodlight

where the freshets call out freedom

to frog-thrilling swamp, skunk-cabbage

trying to sense the conscience of these hills

knowing how the single-minded, pure

solutions bleached and desiccated

within their perfect flasks

for it was not enough to be New England

as every event since has testified:

New England’s a shadow-country, always was

it was not enough to be for abolition

while the spirit of the masters

flickered in the abolitionist’s heart

it was not enough to name ourselves anew

while the spirit of the masters

calls the freedwoman to forget the slave

With whom do you believe your lot is cast?

If there’s a conscience in these hills

it hurls that question

unquenched, relentless, to our ears

wild and witchlike

ringing every swamp.

II.

The mountain laurel in bloom

constructed like needlework

tiny half-pulled stitches piercing

flushed and stippled petals

here in these woods it grows wild

midsummer moonrise turns it opal

the night breathes with its clusters

protected species

meaning endangered

Here in these hills

this valley we have felt

a kind of freedom

planting the soil have known

hours of a calm, intense and mutual solitude

reading and writing

trying to clarify connect

past and present near and far

the Alabama quilt

the Botswana basket

history the dark crumble

of last year’s compost

filtering softly through your living hand

but here as well we face

instantaneous violence ambush male

dominion on a back road

to escape in a locked car windows shut

skimming the ditch your split-second

survival reflex taking on the world

as it is not as we wish it

as it is not as we work for it

to be

III.

Strangers are an endangered species

In Emily Dickinson’s house in Amherst

cocktails are served the scholars

gather in celebration

their pious or clinical legends

festoon the walls like imitations

of period patterns

(…and, as I feared, my “life” was made a “victim”)

The remnants pawed the relics

the cult assembled in the bedroom

and you whose teeth were set on edge by churches

resist your shrine

escape

are found

nowhere

unless in words

(your own)

All we are strangers–dear–The world is not

acquainted with us, because we are not acquainted

with her. And Pilgrims!–Do you hesitate? and

Soldiers oft–some of us victors, but those I do

not see tonight owing to the smoke.–We are hungry,

and thirsty, sometimes–We are barefoot–and cold–

This place is large enough for both of us

the river-fog will do for privacy

this is my third and last address to you

with the hands of a daughter I would cover you

from all intrusion even my own

saying rest to your ghost

with the hands of a sister I would leave your hands

open or closed as they prefer to lie

and ask no more of who or why or wherefore

with the hands of a mother I would close the door

on the rooms you’ve left behind

and silently pick up my fallen work

IV.

The river-fog will do for privacy

on the low road a breath

here, there, a cloudiness floating on the black top

sunflower heads turned black and bowed

the seas of corn a stubble

the old routes flowing north, if not to freedom

no human figure now in sight

(with whom do you believe your lot is cast?)

only the functional figure of the scarecrow

the cut corn, ground to shreds, heaped in a shape

like an Indian burial mound

a haunted-looking, ordinary thing

The work of winter starts fermenting in my head

how with the hands of a lover or a midwife

to hold back till the time is right

force nothing, be unforced

accept no giant miracles of growth

by counterfeit light

trust roots, allow the days to shrink

give credence to these slender means

wait without sadness and with grave impatience

here in the north where winter has a meaning

where the heaped colors suddenly go ashen

where nothing is promised

learn what an underground journey

has been, might have to be; speak in a winter code

let fog, sleet, translate; wind, carry them.

V.

Orion plunges like a drunken hunter

over the Mohawk Trail a parallelogram

slashed with two cuts of steel

A night so clear that every constellation

stands out from an undifferentiated cloud

of stars, a kind of aura

All the figures up there look violent to me

as a pogrom on Christmas Eve in some old country

I want our own earth not the satellites, our

world as it is if not as it might be

then as it is: male dominion,gangrape,lynching,pogrom

the Mohawk wraiths in their tracts of leafless birch

watching: will we do better?

The tests I need to pass are prescribed by the spirits

of place who understand travel but not amnesia

The world as it is: not as her users boast

damaged beyond reclamation by their using

Ourselves as we are in these painful motions

of staying cognizant: some part of us always

out beyond ourselves

knowing knowing knowing

Are we all in training for something we don’t name?

to exact reparation for things

done long ago to us and to those who did not

survive what was done to them whom we ought to honor

with grief with fury with action

On a pure night on a night when pollution

seems absurdity when the undamaged planet seems to turn

like a bowl of crystal in black ether

they are the piece of us that lies out there

knowing knowing knowing

(1980 – uit: Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far, Norton Books, 1981, p. 40 – 45).